With Color Out of Space’s North American release on January 24th, followed by a Blu-ray on February 25th, fans of horror movies have a lot to be excited for. Twenty-five years since we last saw him release one of his classic ‘90s horror movies, not only is an H.P. Lovecraft tale being brought to terrifying life, but it also marks the return of a renegade filmmaker. Richard Stanley is back and what better way to celebrate than to retrospect his first film, a cyberpunk fever dream known as 1990’s Hardware.

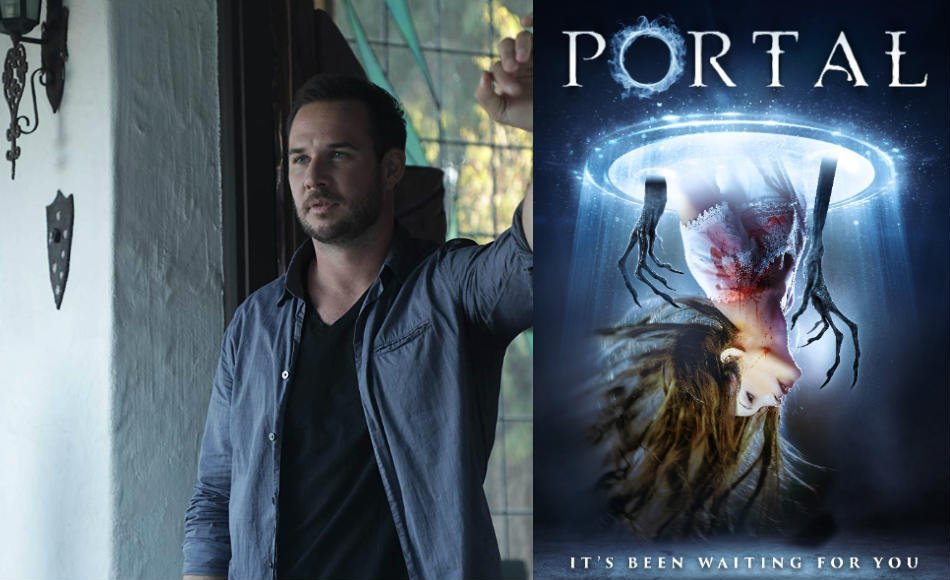

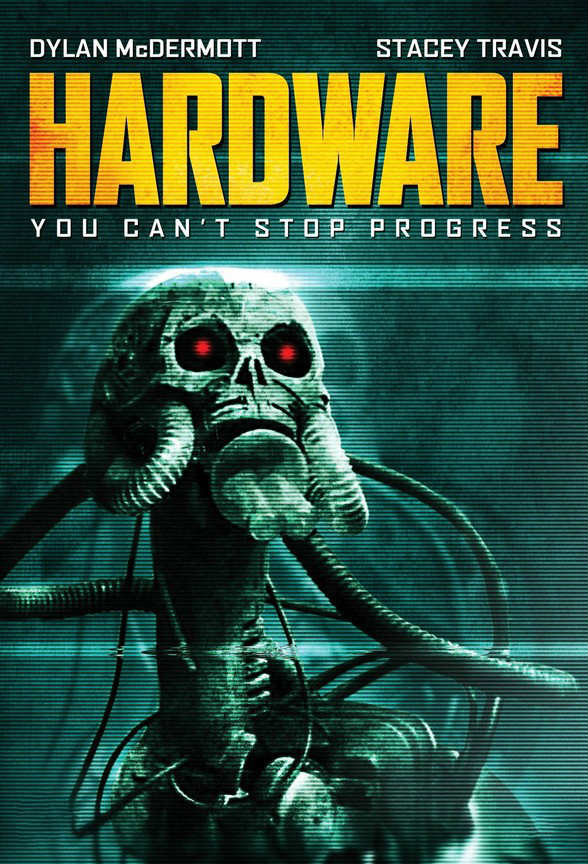

Plot via Severin Films: Dylan McDermott (The Clovehitch Killer, American Horror Story) stars as a post-apocalyptic scavenger who brings home a battered cyborg skull for his metal-sculptor girlfriend. But this steel scrap contains the brain of the M.A.R.K. 13, the military’s most ferocious bio-mechanical combat droid. It is cunning, cruel, and knows how to reassemble itself. Tonight, it is reborn…and no flesh shall be spared. Stacey Travis (Ghostworld) co-stars – along with appearances by Iggy Pop, Lemmy of Motörhead and music by Ministry and Public Image Ltd.

Director/Writer: Richard Stanley

Runtime: 94 minutes (of acid-dropping, head-banging cyberpunkitude)

Rating: R (for sex, violence and robotic eviscerations)

Cast: Dylan McDermott (Moses), Stacey Travis (Jill), William Hootkins (Lincoln Wineberg), John Lynch (Shades), Iggy Pop (Angry Bob), Mark Northover (Alvy), Lemmy (Taxi Driver), Carl McCoy (Nomad)

A Wayward New-Wave Virtuoso Enters the Scene

At times beautiful, at times a grunge-fueled apocalyptica from the depths of insanity, but always fascinatingly subtextual and heart-pumping. On the surface, Hardware is a grand ole’ piece of early ‘90s schlock horror cinema: a killer robot and a final girl locked in an apartment together, political and societal satire, gore, heavy metal, sex, violence and loads of pulpy cyberpunk gooey goodness. But while all that is good and fun, there’s a more interesting mind at play behind the camera which provides the film with its unique brand of stimuli.

To dissect Hardware, one must first dissect Richard Stanley.

One-part mad genius, one-part plain genius, Stanley is a writer-director who has managed to leave a mark on film history with only two completed films (not counting his documentary work). Hardware was his first, followed by Dust Devil, and almost followed by The Island of Dr. Moreau (the story of what happened there now legendary and covered in the documentary Lost Soul). After that, Stanley floated off, keeping up with the aforementioned documentary work and a few short films, but mostly writing a series of projects never produced for one reason or another.

Each potential Richard Stanley film is cooler than the last, as well. For instance, there’s one about Dutch bank robbers who, during a heist in Amsterdam, discover a Lovecraftian creature locked away in an underground vault.

Listening to Richard Stanley speak is an experience, you walk away wondering how such a creature can exist. A brilliant intellectual whose interests are eclectic and vast, entrenching himself in art, history, film, literature, adventuring (he spent a few years hunting the Holy Grail), culture, mythology, sci-fi, occultism and most important of all, modesty.

That last one is what makes him such a figure to study, as he’s unaware that he’s bizarre and riveting. If Werner Herzog decided to make a movie about him it would not be the least bit surprising.

It’s the life of Richard Stanley that brings us right into Hardware. He was just 24 when he made the movie and had already lived a full life by that time, well-known as an incredible and experimental music video director, where he introduced motifs he’d return to in Hardware and Dust Devil. Branching out into documentarian work that stood close to his heart, Stanley found himself involved in the Afghan War when he traveled there to make the short documentary Voice of The Moon in the late ‘80s.

There, entrenched with a guerrilla faction, Stanley was part of the Battle of Jalalabad and faced a fateful artillery shell that 90nearly took him and his cameraman’s life. From this event, Stanley flew from Afghanistan and right into pre-production for Hardware. That’s some surreal whiplash not lost on Stanley upon reflection, and within that convergence of worlds, we get a piece of where the uniqueness of Hardware’s horror originates.

Written from a place of childhood literary inspiration and some deep real-world—and, unfortunately, prophetic—fears of drone technology, but then directed within the lens of a PTSD hallucination. A mélange of impulses that can exhaust your senses as much as thrill and shock.

Hardware started life many years earlier from a school-time short entitled Incidents in An Expanding Universe, which planted the seedlings that would one day grow into a full film. After that, Stanley tried to get many scripts produced, none of which saw fruition, but he was sure to remember all the notes would-be distributors would have for them; certain types of stunts, gratuitous shower scenes, chainsaw kills and the like.

Stanley crafted all these disparate elements into the script for what would be Hardware. Of course, he did this while listening incessantly to Iron Maiden, which would work wonders for anyone.

This is What You Want, This is What You Get

The PTSD aside, it’s obvious the material scares the piss out of Stanley. It’s what helps the film stand out from other killer robot horror movies, as you rarely see such a schlocky concept played like its high classical literature. The world of the horror film could support a multi-media wealth of stories divorced from its lead logline, existing in a ravaged falling-apart world entrenched in post-nuclear fallout.

A world that seems content to continue on like nothing is wrong, living some sort of fallacy of what was once considered normal existence. On one hand, it’s the most realistic future we’ve seen in that regard, on the other, it fills the tale with impending hopeless doom, and a biting satire both political and societal in nature.

This is Earth as not a living hell, but a purgatory. Day to day living cranks along as the government sells hallucinogenic cigarettes to keep the bursting population in a euphoric state and the TV advertises radiation-free reindeer steak between frenetic and seizure-inducing regular scheduled programming. Everyone is waiting to die long before a scavenger out in the irradiated wasteland finds a broken robot in the sand and brings it into town.

That robot is purchased by Mo (short for Moses) played by the ever-ageless Dylan McDermott, a robot handed soldier with a penchant for reading the Bible. He wants to give it as a Christmas gift for his metal-working artist girlfriend Jill (the badass Stacey Travis). Also, yeah, this is technically a Christmas horror movie.

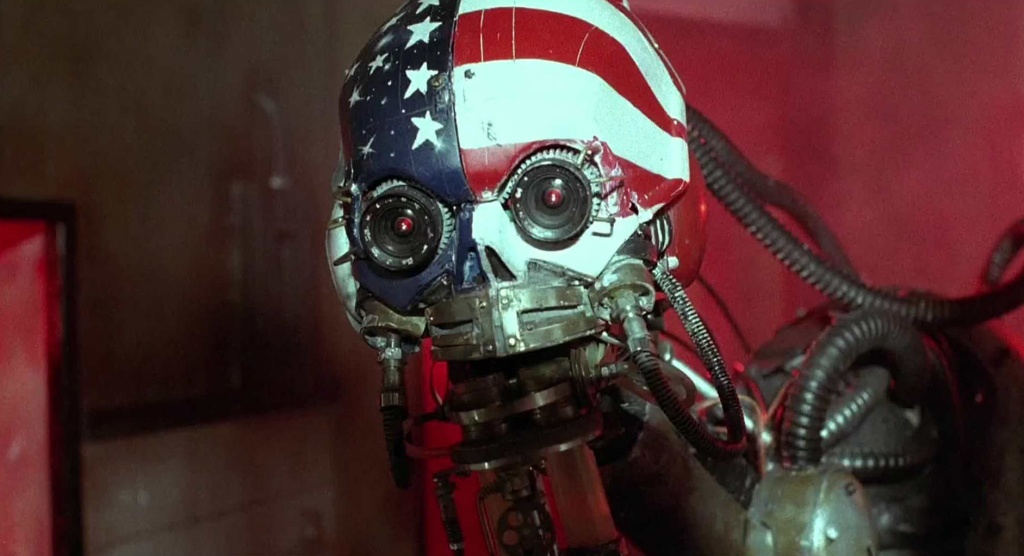

The disembodied bot parts are put together into a sculpture as Stigmata by Ministry appropriately plays. As part of that sculpture, Jill paints the head into the ole’ red, white and blue. Interestingly enough, the satirical part of that paint job is secondary to the meaning Stanley aimed to get across: the bot would have a two-faced paint job, as it represents night and day, life and death.

Unfortunately for Jill, the titular Hardware, now adorned with old glory, is still active and programmed to reconstitute itself with whatever parts are laying around. Like tentacles, the wiring from the skull-like head reaches out and begins attaching excess limbs, crafting a new body so it may continue on its purpose of population control.

Scrap-Metal Abaddon

“No flesh shall be spared” is both a bible quote that starts the film and part of where the government-created killer bot gets its namesake, the M.A.R.K. 13. A machine that is more demon than a series of levers and rivets, its programming is to take life but it’s also a creature of resurrection, able to rebuild itself endlessly. Though it does have a weakness, a life-giving resource that’s not very abundant in this desert world.

In Stanely’s eyes, the M.A.R.K. 13 is more than mindless. A heat-seeker, it sees through thermal tech, ensuring it strives for light, ever reaching out for its purpose, not knowing why or what it’s doing, just that death is its function. A miscalculated, violent and mysterious to itself higher calling.

Beyond the religious symbology built into its thought process, its main design to kill is also indicative of the film’s political nature. It only goes for saw blades or drills if it can’t utilize its main weapon: an injection of poison that renders the victim into a hallucinatory state viewed as “almost pleasant” by its faceless creators. Euthanasia.

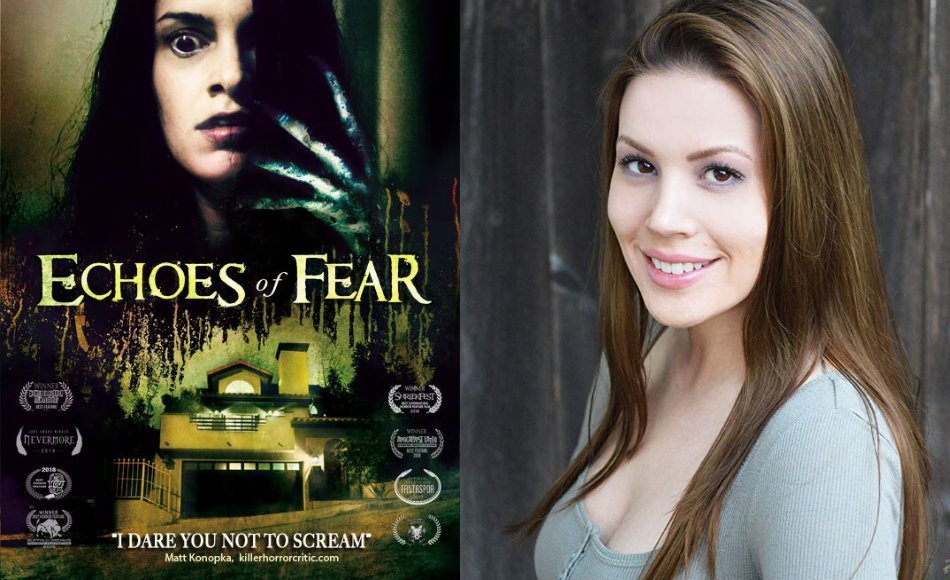

Within this Argento and Brava inspired neon-lit apartment, a revolutionary battle for humanity is condensed down to two figures on either side of a sociopolitical nightmare future. Jill is a criminally forgotten final girl and horror movie heroine in the annals of cinema. She is a resilient survivor who is thrust into the lead role in a brilliant piece of switcheroo with Mo, the soldier we expect to action his way through the plot.

Travis puts in an incredible performance and, by Stanley’s own admission, this is what helps the movie stick the landing, grounding it in a very humanistic way. With flashy red hair, a torn kimono, and bloody knuckles wrapped in bandages like a street boxer, by the end of the horror flick, Jill has fought off the devil single-handedly and come out stronger. This sets her up for a sequel that would see her become the cyberpunk world’s Ellen Ripley.

The Good News: There is No F*cking Good News!

Yes, Hardware was nearly a franchise. Stanley would put the script online for Hardware II: Ground Zero and you can find it with some simple digging. The plot would pick up with Jill living in a colony of “destructionalists,” who have forgone all technology with hopes of returning humanity to nature. But with the Government putting the M.A.R.K. 13’s into full production in order to patrol the US-Mexico border, another prophetic twist, Jill will end up banding together allies and leading a charge against an army of the murderous bots in a full-on rebellion.

Unfortunately, Hardware II was a victim of the first film’s cult success. Corporate entities would battle over who gets profits and rights to the film, an often-seen side effect of indie movie success in the ‘90s. This legal maelstrom would ensure the sequel could never be produced and drift into a sad, “what if?” for fans, depriving us from future horror movies in the would-be franchise.

Stronger Than Reason, Stronger Than Lies, the Spirit of Punk Never Dies

But none of this takes away from Hardware itself, an inspirational horror movie for many filmmakers at the time and even today, placing it side-by-side with other titans of ‘90s indie movies to bring about a whole new generation of writers and directors. For many years, it stood as a view into an alternate reality where Richard Stanley would reach heights of success the same way Sam Raimi or Peter Jackson managed, taking horror movies by storm.

With Color Out of Space now releasing, the first Richard Stanley feature film since Dust Devil, that may no longer be an alternate reality. Not only is Hardware an awesome horror film, but it’s an introduction to a true artist that never gave up, that stayed in the game. With the patience of a saint, Richard Stanley has returned with gusto, seemingly still with the same fire that gave us Hardware.

This writer cannot wait to see what’s next. Who knows what else the nomadic scavenger may find buried in the sand? Meanwhile, fans can look forward to Color Out of Space and revisiting one of the most underrated horror movies of the ‘90s, Hardware.